The Downside of Cap Rates in Real Estate Valuation (Use This Instead)

Ah, the cap rate.

One of the most widely used metrics in the real estate investment industry, and a benchmark that many brokers and investors use to value a real estate deal.

But at the end of the day, how important is a cap rate, really?

And should you really be using it to value real estate deals, or should you rely on something else to guide your investment decisions?

In this article, we’ll walk through exactly what a cap rate is, what this metric can tell you, and five reasons why you might want to think twice about using a cap rate exclusively to value a commercial real estate deal.

If video is more your thing, you can watch the video version of this article here.

What Is a Cap Rate?

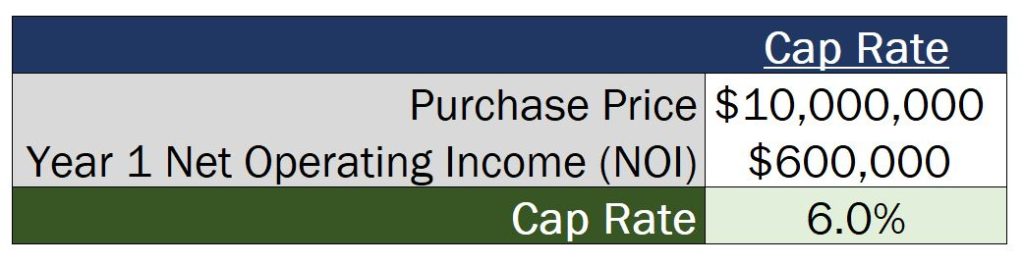

The capitalization, or “cap” rate, on a real estate deal is calculated by taking the annual net operating income on a property, and dividing that by the purchase price of the property.

And this metric can give commercial real estate investors a general sense for the unlevered yield a property will generate, or the yield before debt is factored into account, and is used by many investors to get a rough idea of where a property might trade at the end of the day.

For example, if you’re analyzing a deal that’s priced at $10 million, and you project the first year of net operating income after you buy the deal to be $600,000, that deal would be priced at a 6.0% cap rate.

This essentially tells you that, without factoring in loan proceeds and any sort of debt service payments in the first year of ownership, the property would generate a 6.0% dividend yield on your initial investment in the first year of ownership.

Seems helpful, right?

Well, the problem is that the cap rate fails to take into account a lot of other really important factors in a real estate deal, that end up being significantly more important than what your first year’s NOI divided by your purchase price is going to be.

So, here are the 5 main downfalls of relying on a cap rate approach to value a real estate deal, in no particular order.

Cap Rates Don’t Factor In Debt

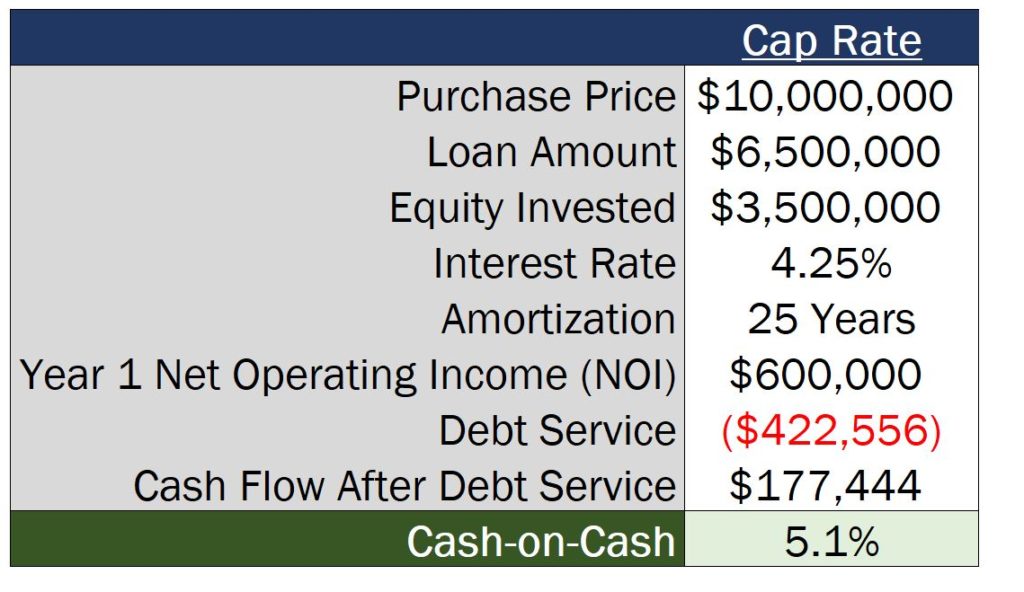

The vast majority of real estate investments are purchased with a loan on the property, which is going to change that first year’s return a lot from the 6.0% mentioned above, especially in a higher interest rate environment.

Also, real estate can often be a negative leverage investment, meaning that the cash-on-cash return, or cash in your pocket every year as a percentage of equity invested, is actually lower with debt than it is without it.

And when taking amortization payments into account on the loan, for that 6.0% cap rate deal, a 65% LTV loan with a 25-year amortization period an interest rate of just 4.25% would actually produce a lower cash-on-cash return figure than the 6.0% cap rate itself.

Cap Rates Don’t Factor in Capital Expenses

Especially for office, retail, and industrial properties where leasing commissions and tenant improvement allowances are necessary parts of the game in order to run your deal, this can be a huge skew to the numbers, again turning that 6.0% cap rate into a significantly lower figure in the first year of the hold period.

In many “value-add” investment opportunities with either a lease-up of vacant space or a noteworthy renovation planned upon acquisition, six or even seven-figure capital outlays aren’t uncommon in the first 1-3 years of the hold period, which drastically affects the cash flow generated at the property, and the returns that investors will earn.

And this can be especially true for smaller properties, where a $100,000 TI allowance to lease up a space can be a huge hit to cash flow, and can even require an investor to invest additional capital into a deal, even with a projected 6.0% unlevered yield according to the cap rate calculations.

Cap Rates Don’t Take Into Account Market Rent Growth

This one can be a little bit misleading, because there are some more technical methods of calculating the cap rate, like the Gordon Growth Model, which do factor in market rent growth at the property.

The Gordon Growth Model calculates the cap rate as the discount rate assigned to the property less the growth rate of the net income generated by the property, so in a sense, this does incorporate expected annual income growth during the entire hold period.

However, the problem here is that very, very few investors are running this math when assigning a cap rate to a deal, which leads to extremely oversimplified valuations that are, in large part, incomplete.

Many properties located in coastal markets across the US are priced at significantly lower cap rates than deals in the Midwest or other lightly populated areas seeing negative net migration patterns over time, or more people moving out than moving in.

When an investor that thinks a 7.5% cap rate in Cleveland is a better deal than a 4.5% cap rate in San Francisco simply because of the difference in the going-in unlevered yield, that investor also fails to realize that the rent growth prospects in San Francisco are significantly higher (and have been historically).

And with that, that going-in 4.5% cap rate at purchase will likely turn into a 6.0% unlevered yield (or higher) just a few years down the road from now, while the 7.5% cap rate deal in Cleveland will likely stay at that 7.5% unlevered yield for quite some time, or possibly even drop over time.

Cap Rates Don’t Take Into Account Renovation Premiums or Mark-To-Market Lease-Ups

When just looking at a deal on a cap rate basis, you might think that buying a 3.0% cap rate is insane.

Why would you do that? Well, what if I told you that the building is only 45% occupied, the in-place rents are extremely below market rates, the property is in a great market, and in less than a year you could get the deal to a 7.0% unlevered yield.

Would that 3.0% be insane now, or would the deal actually make sense?

And how much does the cap rate actually tell us about the profitability of the deal? Not much.

Cap Rates Don’t Take Into Account Sale Value

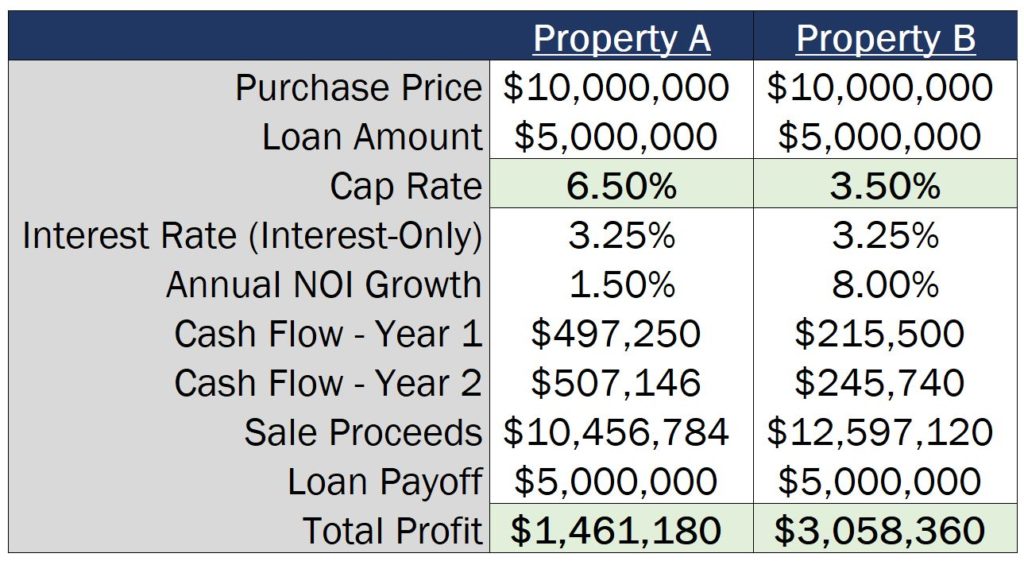

Let’s say you buy two deals, each for $10 million with a 50% LTV loan, so $5 million of equity invested in each.

The first, which we’ll call Property A, is in a market that’s seeing negative net migration and job growth is stagnant, and you buy that property at a 6.5% cap rate. The second, which we’ll call Property B, is in an emerging market with a ton of job growth, and you buy that property at a 3.5% cap rate.

Two years later, you sell both properties.

Because Property A was purchased in a tough market, NOI growth was relatively flat, and rose by just 1.5% per year over the 2-year period. And with that, assuming cap rates in the market stayed flat, you end up selling the deal for just under $10.5 million, for a total profit of about $1.5 million (including cash flow in years 1 and 2).

Because Property B was purchased in a hot market with strong growth, NOI growth shot through the roof, clocking in at 8% per year over your two years of ownership. And with that, assuming cap rates in the market also stayed flat, you end up selling the deal for just under $12.6 million, for a total profit of just under $3.1 million (including cash flow in years 1 and 2).

Which one is the better deal? And does the cap rate tell the whole story?

What To Use Instead – The Internal Rate of Return (IRR)

I hope I’ve convinced you that a cap rate is not the most important investment metric when you’re looking at a real estate deal, and needs to be considered in context.

So, if you can’t rely on the cap rate exclusively to value real estate deals, what should you use instead?

Well, a far more reliable (and meaningful) metric is to value properties is the internal rate of return, or IRR.

The IRR captures all 5 of the factors we covered in this article, wraps them all up in a bow, and spits out an annualized, time-weighted rate of return over the projected hold period that investors can compare to stocks, bonds, and other private equity investment vehicles.

Private equity real estate firms commonly use a target IRR valuation approach, essentially back-solving to a purchase price that allows the investor to hit a targeted internal rate of return that factors in debt, capital expenses, market rent growth, leasing costs, and sale proceeds, as well as the timing of those items, which gives an investor a much more holistic view of their projected returns and if the deal makes sense.

And if you want to learn more about real estate valuation using a target IRR approach, as well as the other underwriting and analysis techniques used by private equity real estate firms across the globe, make sure to check out Break Into CRE Academy, which includes coursework on real estate financial modeling and analysis, pre-built acquisition and development models for multifamily, office, industrial, and retail deals, and private, one-on-one, email-based career coaching to help you break into the industry, whichever stage of the game you’re in.

I hope this helps you get a clearer picture of how you might want to value your next commercial real estate deal, and how the cap right might (or might not) come into play in that analysis.

Good luck!