The MOST Important Return Metric in Commercial Real Estate

Commercial real estate investors value their deals based on the investment returns those properties can generate at a given purchase price.

And with that, most investors usually base their valuations around a target IRR, equity multiple, or cash-on-cash return, or a mixture of all three of these metrics.

However, while each of these metrics tells an important story, each of these metrics also tells a significantly different story, which can make it hard to decide which ones to focus on, and which ones to ignore.

So, to help you determine which metric is most important for you in the valuation of your own (or your firm’s) CRE deals, in this article, we’ll break down three questions to ask yourself when deciding on a return metric to prioritize, and when each metric matters most.

If video is more your thing, you can watch the video version of this article here.

How Is The Sponsor Being Compensated?

The first question to ask yourself when deciding on a commercial real estate return metric to target is, “How am I, or the sponsor running the deal, being compensated?”

For real estate private equity firms and syndicators, one of the most significant revenue drivers for their companies is promoted interest, or the incremental profit split over and above the company’s percentage ownership in a deal.

The vast majority of compensation for these firms is dependent on this promoted interest, and this additional cash flow split is only triggered by exceeding a specific preferred return on the project (if you’re not clear on what an equity waterfall structure is or how it works, see this article for more detail on this topic).

For many investors, especially major institutional groups and pension funds, these organizations have promised their investors (or pension holders) a specific return on their money, or a specific income over a set period of time.

The success or failure of these companies lies in their ability to meet or exceed these promises.

With that, a time-constrained IRR value considering all cash flows on the deal is generally prioritized first for these groups, since this metric measures not only cash flows from operations, but also includes sale proceeds, as well.

While the IRR is also a commonly used return hurdle by smaller private equity shops and real estate entrepreneurs with just a handful of investors, you’ll also sometimes start to see a cash-on-cash or equity multiple-based preferred return come into play at smaller firms.

The intent here is generally to keep things simple for investors, by either referring to a pure multiple of invested capital, or referring to a pure cash flow dividend yield distributed on an annual basis.

Concrete Numbers Can Give Investors Comfort

Many individual investors without a finance background feel most comfortable knowing the exact amount of money they can expect to receive by the time the property is sold.

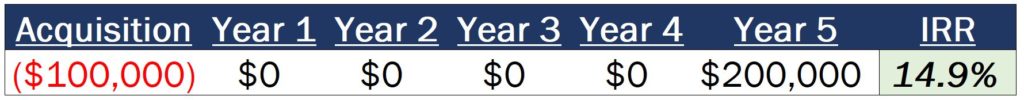

With that, these investors would rather hear that if they invested $100,000 in a deal, they’ll get $200,000 back in total over the next 5 years, versus hearing they’ll earn an annualized, time-weighted return of 14.9% over the hold period.

On the other hand, some investors might be looking to invest in real estate to provide regular, predictable income in order to supplement their W-2 wages or to fund their retirement.

And for these investors, what will often feel most comfortable is the knowledge that for every $100,000 they invest in a property, they can expect to receive about $8,000 per year in cash flow in their pocket over the life of the investment.

Regardless of the structure here, when making valuation decisions on commercial real estate properties, ask yourself how the sponsor on the deal is being compensated.

This will tell you what investors in the property care about most, and how you should structure your valuation accordingly.

When Do I (or My Investors) Need The Money?

Aside from understanding compensation structures on the deal, the next question when deciding on a commercial real estate return metric to focus on is, “When do I (or my investors) need the money from this deal?”

For the investor that’s looking to fund their retirement or supplement their income, the cash-on-cash return is an extremely important metric, and very well may be what you’ll want to prioritize most.

In addition, investors focused primarily on cash flow generally want to be able to rely on the income generated by the asset long-term and minimize transaction costs, meaning that they won’t be interested in a sale of the property any time soon.

With that, return targets that require a projected sale value to be meaningful (or really the IRR, specifically) will usually be the least valuable performance metrics to measure in these types of situations.

When Cash Flow Can Backfire

On the other side of the equation, for an ultra high-net worth individual that’s looking to find a place to park their money for long-term wealth preservation and growth, a deal producing a significant amount of cash flow each year can actually be a turnoff to this investor base, and may actually do more harm than good.

High cash-on-cash return values generally indicate high cap rates, which often only exist on deals where lower-than-average income and value appreciation is expected in the future.

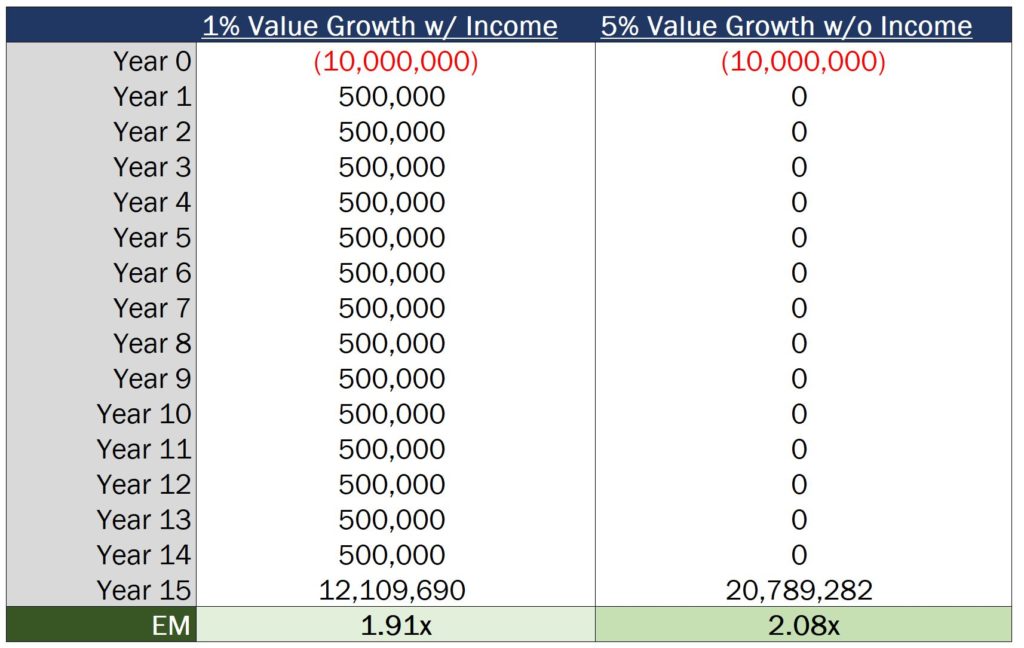

With that, if an investor is looking to park their money in an asset long-term (and they won’t need that money for another 15-20 years or more), a deal with a high cash-on-cash yield is likely to produce lower overall profit figures over that same time period than another deal with a low (or non-existent) cash-on-cash return during this time.

Cash Flow Can Create Taxable Income

Additionally, some high net worth investors with equally high incomes may actively want to avoid generating annual ordinary income from a real estate deal, specifically from a tax perspective.

In the case that the interest expense is low on the deal (due to low leverage levels), or in the case that the annual depreciation expense is low on the deal (due to a high allocation of the property value to the land), there could potentially be a significant amount of taxable income generated by the property each year.

And for high income earners in high income tax states (where additional income could be taxed at 55% or more in some cases), many investors would rather save that tax burden for a time in the future and pay capital gains tax rates, rather than paying half of their income from the property to the government during these high income years.

For these types of investors, an equity multiple or IRR-based target will usually make the most sense, with those in the wealth preservation category most likely looking at the equity multiple for a whole-dollar figure that they can expect to leave to their heirs in the future, or count on for retirement over a 10-15 year hold.

How Much Do I Believe In The Upside of This Deal?

Once you’ve asked yourself about the compensation structure on the deal and the preferred timing of the cash flows, the last question to ask yourself to choose a target commercial real estate return metric is, “How much do I believe in the upside of this deal?”

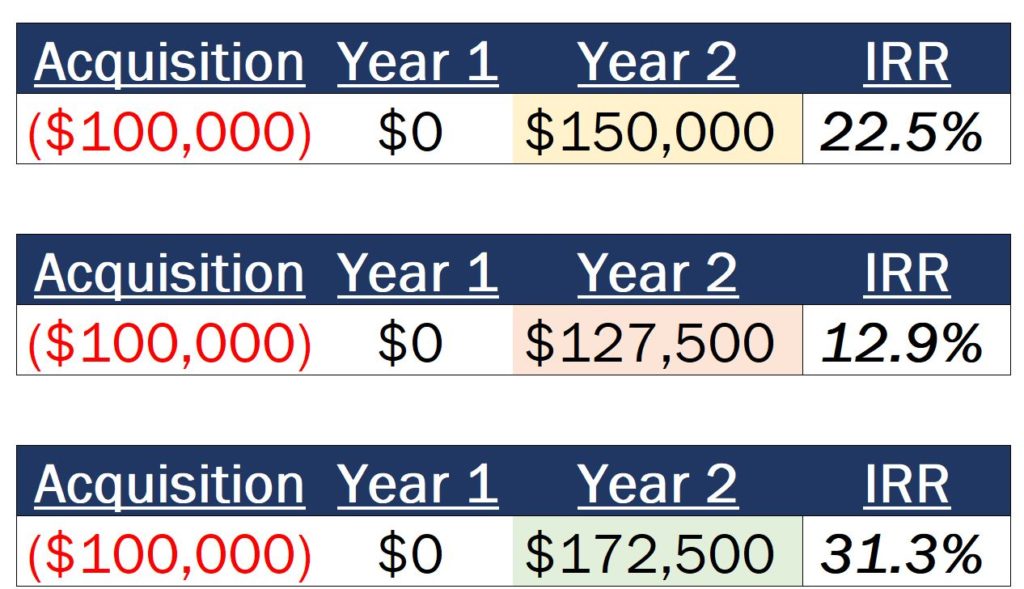

Of all three of the return metrics we’ve covered in this article, the IRR is generally going to be the most sensitive to the sale price of the property (by a pretty wide margin).

This is especially true for very short-term hold periods, where a 10%-15% fluctuation in sale value can result in massive swings in the IRR of the project.

What this means is that, if you whiff on what you believe the property will sell for just 2-5 years down the road, investor returns can end up being dramatically different than what was projected in the pro forma, which is not an ideal scenario for anyone involved.

If you feel unsure about the long-term value potential of the deal (as is the case for many investors looking for deals with a higher going-in cap rate in traditionally lower-growth markets), the cash-on-cash can be a much more helpful metric to solve for than the other two metrics on this list, since this won’t require any sort of sale value assumption to achieve the return targets you set out to hit.

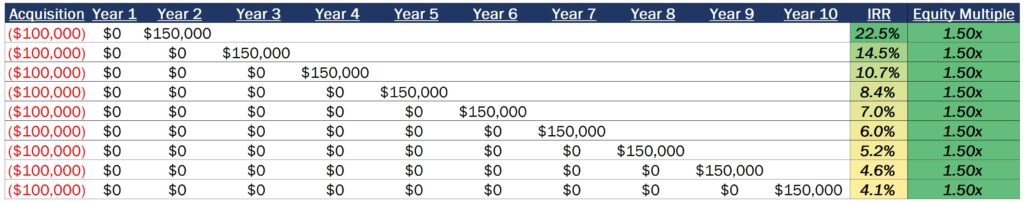

Additionally, if you do believe in the upside of a deal, but you also believe that the upside on the project could take 10 years or more to materialize, the IRR also might not be the right fit here, since the IRR can tend to drop as the hold period is extended.

Because of this, the equity multiple will often be the best fit for scenarios like these, since this metric will capture the cash flows during the hold period and at sale, and won’t penalize an investor for a later distribution of sale proceeds.

Which Commercial Real Estate Return Metric Is Most Important For You?

At the end of the day, the return metrics that should be used to value a commercial real estate deal come down to the specifics around how the sponsor is being compensated, how quickly investors in the property expect a return on their capital, and how much you believe in the upside of the deal (and the level of risk you’re taking on at sale).

And if you want to learn more about how to analyze and value commercial real estate deals, whether you’re looking to break into the industry at a top real estate private equity or brokerage firm or do your own deals in the future, make sure to check out our premium training platform, Break Into CRE Academy.

A membership to the Academy will give you instant access to over 120 hours of video training on real estate financial modeling and analysis, access to our entire library of pre-built acquisition, development, and waterfall models for multifamily, industrial, office, and retail deals, and you’ll also have direct access to private, one-on-one, email-based career coaching to help you navigate your next steps in the industry, or break into the commercial real estate business for the first time.

Thanks so much for reading, and I hope this helps you get a better idea of which return metrics you might want to focus on for your next deal.

Good luck!