5 Commercial Real Estate Loan Terms You Should Know

If you’re new to the real estate industry altogether or moving from the residential part of the business, commercial real estate loans can feel like a whole different animal than what you’re used to.

Instead of just your your standard, 30-year, fixed-rate loan that you’ll often see on a residential home loan, commercial real estate loans come with a host of different terms, structures, and clauses that can significantly impact the cash flows of a real estate deal.

So to help you get a handle on some of the most important (and commonly used) out there, this article will walk through five commercial real estate loan terms you should know if you’re trying to break into CRE today, and how these are applied to commercial real estate deals.

If video is more your thing, you can watch the video version of this article here.

Interest-Only Period

The first term on this list is an interest-only period.

And an interest-only period is exactly what it sounds like – a period or months or years in which he borrower only pays interest payments on the loan, rather than interest and principal payments that would pay down the loan balance each month.

This is often offered by lenders in the first one to three years of a commercial real estate loan, especially for deals with a heavy “value-add” or renovation component that will significantly reduce cash flow in the first few years of ownership.

And as a borrower, this can make a pretty significant different in cash flow during times when it might be needed most, which can help preserve distributions to investors during the renovation period itself, or just make sure the property is in a cash flow positive situation while making its turnaround efforts.

And this can make an even more significant on the cash-on-cash returns of the property, or the cash flow generated by the asset as a percentage of equity invested in the deal.

How This Works In Practice

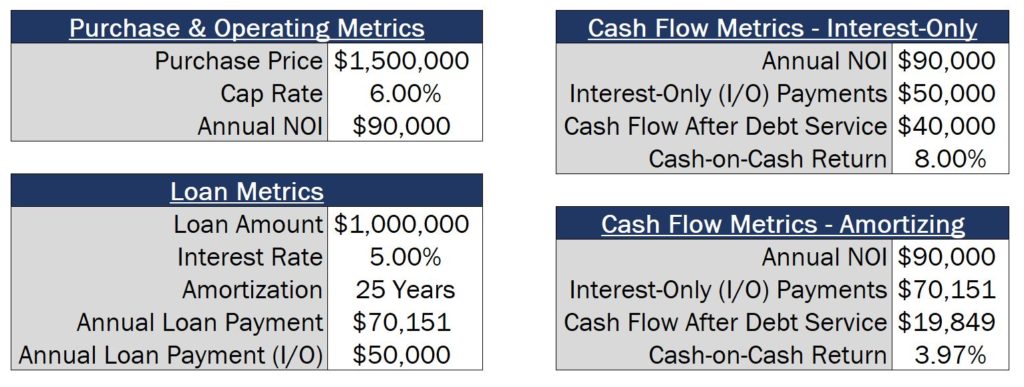

To use an example, let’s assume you buy a $1,500,000 property with a $1,000,000 acquisition loan.

Let’s also say that interest rate is 5.0% and your amortization period is 25 years, giving you a total annual loan payment (both interest and principal) of $70,151 per year.

However, if that loan were interest-only in that first year of the loan term, that loan payment would only be $50,000 in year one ($1,000,000 * 5.0%), increasing cash flow after debt service at the property by $20,151.

But when we look at this difference as a percentage of equity invested, this is where things get really interesting.

If we assumed we were buying the property at a 6.0% cap rate, or generating $90,000 of net operating income (NOI) in year 1 of the loan term, your cash-on-cash return in the amortizing loan scenario would be just 3.97% (($90,000 – $70,151) / $500,000).

But in the interest-only scenario, assuming all else remains equal, that property would now be generating an 8.0% cash-on-cash return (($90,000 – $50,000) / $500,000).

More than doubling the cash-on-cash returns generally leads to happy investors and less stressed-out operators.

Both very, very good things.

Prepayment Penalties

Prepayment penalties are also exactly what they sound like – financial penalties for paying the loan off before the original maturity date.

These penalties are used to make sure the lender continues to receive the yield they signed up for when they originally issued the loan proceeds, for as long as that capital was projected to be out in the market.

And these can vary significantly depending on the loan product and lender you’re working with, but generally this will be calculated as a percentage of the overall loan amount, or using more complex calculations, most commonly yield maintenance and defeasance.

“Step-Down” Prepayment Penalties

For a flat percentage of the overall loan amount, often lenders will structure this as a “step-down” amount, with the percentage of the loan amount owed decreasing as the loan nears its maturity date.

For example, you may hear a lender refer to a commercial real estate loan with 7-year loan term as having a 5-4-3-2-1 prepayment penalty. In this scenario, this would mean that the penalty would be calculated as 5% of the outstanding loan balance if the loan is prepaid in the first year of the loan term, the penalty would be 4% of the outstanding balance if the loan is prepaid in the second year of the loan term, the penalty would be 3% in year three, 2% in year four, and 1% in year five of the loan term.

And with that, the closer to the maturity date the loan is repaid (and therefore the longer the lender is able to receive interest payments on their outstanding capital), the lower that prepayment penalty will be.

Yield Maintenance Prepayment Penalties

With a yield maintenance prepayment penalty, the fee when the loan is paid off early is generally calculated by taking the present value of the remaining payments on the loan.

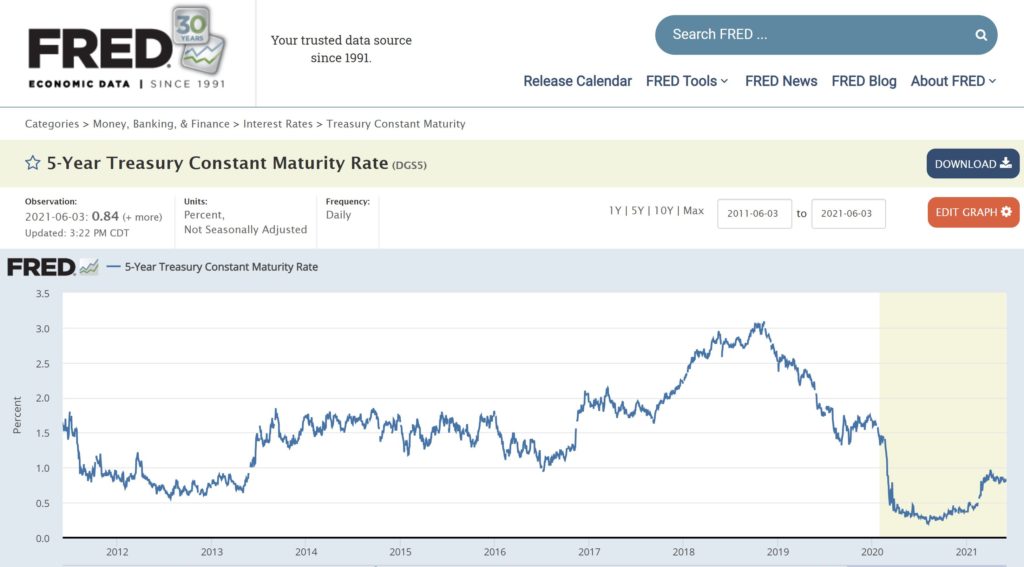

And this present value calculation takes into account the interest rate on the loan, as well as the current risk-free interest rate (usually the US Treasury yield with a corresponding maturity date) that the lender could receive at the time the loan is paid off.

To calculate a yield maintenance prepayment penalty, lenders will find the difference between the interest rate on the current loan and the interest rate on the currently available US Treasury yield with a corresponding maturity date (3 years until loan maturity equals 3-Year US Treasury yield), and then calculate the difference in interest payments between those investments for the remainder of the original loan term.

From there, lenders will use that same current US Treasury rate on the equivalent loan term to discount the difference between those payments to arrive at the yield maintenance prepayment amount.

Defeasance

A defeasance clause in the loan terms serve a similar purpose as the yield maintenance prepayment penalty, essentially making sure the lender remains whole and can receive that same yield on their outstanding capital that they would have earned if the loan were held until maturity.

From a mechanics perspective, a defeasance clause essentially allows the borrower to substitute the real estate as collateral with a portfolio of US securities which will generate the same yield to the investor through the remaining term of the loan.

This means that if interest rates have risen substantially since the loan proceeds were issued and the lender could actually receive a higher yield on their capital if they were to invest in US securities with a similar risk profile, the defeasance prepayment penalty will be low (or non-existent).

However, if interest rates have dropped since the start of the loan term and the lender would take a hit on their yield generated if they had to go back out to the market, the borrower will have to pay up to the point where the lender can hit that same original yield in the lower interest rate environment.

Both yield maintenance and defeasance clauses can get pretty nuanced, so the exact details will vary based on the specific language within the loan terms, but this is the general framework in which these two clauses operate.

Floating-Rate Debt

A “floating” interest rate refers to an interest rate that will be adjusted throughout some or all of the loan term, rather than staying the same (or fixed) throughout the loan term.

If commercial real estate borrowers think interest rates will stay low or decrease, floating-rate debt can be used to take advantage of falling interest rates to reduce interest payments owed each month.

These types of structures are common on construction loans and other short-term commercial real estate loan products, and borrowers will also often purchase something called an interest rate “cap” on these floating rate loans to make sure they’re not exposed to significant, unplanned interest rate increases during the loan term.

Follow-On Loan Proceeds (Good News Money)

As it’s often referenced in commercial real estate, “Good News Money” refers to additional loan proceeds issued by the lender in order to help a borrower pay for capital costs associated with signing a new commercial lease at the property.

Lenders and borrowers both win with increased rental revenue when a new lease is signed, however there can often be significant costs associated with re-leasing efforts and getting a tenant up-and-running in their new suite.

Specifically, tenant improvement allowances (to help the tenant build out their space) and leasing commissions (to pay a leasing agent for finding the tenant to occupy the property) are two significant cash outlays that Good News Money will help fund, to reduce the cash strain on the borrower.

It’s important to note that this isn’t always a dollar-for-dollar funding, however many lenders will fund between 60% and 70% of the cost to re-tenant certain spaces up to a certain whole dollar amount to assist a borrower with improving the property overall.

Lockout Period

Similar to the pattern you’ve seen so far with the other four terms on this list, a lockout period is relatively straightforward, as well – this is a period of time in which a borrower is “locked out” of paying off the loan in full, and the loan is not repayable during this time for any reason.

These types of structures can be extremely restrictive for borrowers, especially in scenarios where they may receive an unexpected purchase offer they feel like they can’t refuse, or during an economic downturn where cash flow is tight.

Unlike residential mortgage loans for single family homes that can generally be paid off at any time, a commercial real estate loan with a lockout period may require two, three, five, or even ten years before the loan is allowed to be paid off in full. And with that, this is often a negotiating point for borrowers to reduce their exposure to a lockout period, or at least minimize the time where this will be present.

How These Loan Terms Affect Commercial Real Estate Deals

Knowing what these loan terms mean is one thing, but knowing how these terms will affect cash flows on a real estate deal is another.

And if you want to learn more about how to incorporate these and other commercial real estate loan terms into your own financial analysis and underwriting of properties you’re taking a look at, make sure to check out Break Into CRE Academy, which includes coursework that will walk you step-by-step through how to model things like a yield maintenance prepayment penalty, floating rate debt, refinances, and interest-only periods to help you accurately reflect whatever type of structure is thrown your way.

I hope this helps – good luck on your next deal!