Real Estate Equity Waterfalls FAQ – 5 Things You Should Know

Most real estate financial analysis is relatively straightforward, and you’ll often hear industry veterans say something along the lines of, “Real estate isn’t rocket science!”

And while this might be true, one of the most complex, if not the most complex topic in real estate financial analysis is real estate equity waterfall modeling, and some of these structures can feel like rocket science with the level of complexity baked into these agreements.

We have a few courses on real estate equity waterfall modeling and a popular video on the Break Into CRE YouTube channel explaining these in detail, but this topic still tends to be pretty difficult to totally comprehend.

So in this article, to help break down what a real estate equity waterfall structure is (and how they work), we’ll break down 5 of the most commonly asked questions I see around real estate equity waterfalls and waterfall modeling, and my answer to each.

If video is more your thing, you can watch the video version of this article here.

What Is a Real Estate Equity Waterfall Structure?

At a high level, the basic premise of a real estate equity waterfall starts with a basic partnership structure between equity investors in a real estate deal.

This partnership structure determines how cash flows are split between the equity partner that operates the property and is primarily responsible for the major decision-making on the deal (generally referred to as the General Partner, or GP), and the equity partner that acts as the non-operating capital partner and is not responsible for the day-to-day management of the property (generally referred to as the Limited Partner, or LP).

With that, a real estate equity waterfall structure is created to reward the operating GP for exceeding certain investment return targets, or hurdle rates, with a portion of the investment returns that would have otherwise been allocated to the LP going to the GP instead (assuming those return targets are hit).

The Preferred Return & Promoted Interest

Real estate equity waterfall structures generally include what is referred to as a preferred return, or a rate of return that, if achieved, will allow the GP to receive a portion of the cash flows which would have otherwise been allocated to the LP. This is called promoted interest.

For example, you might see a deal with a preferred return of an 8% IRR, with anything over an 8% IRR yielding 20% promoted interest to the GP.

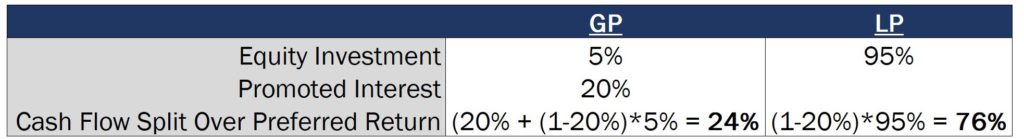

And this means that 20% of the cash flows earned above that 8% will automatically be allocated to the GP, regardless of the equity investment they’ve made in the deal. And in most structures, the equity investor will also receive their share of the remaining 80% of the cash flows, in proportion to their initial equity investment.

For example, if the GP invested 5% of the equity in the above scenario, the GP would receive 20% of the cash flows over an 8% IRR, plus 5% of the remaining 80% of the cash flows after accounting for the promoted interest (5% * 80% = 4%), for a sum total of 24% of the cash flows over the preferred return going to the GP.

This type of structure heavily incentivizes the operating partner to make decisions that will maximize returns for the partnership as a whole, and rewards strong investment performance that meets or exceeds return expectations.

Cash-on-Cash vs. IRR

With the basics out of the way, let’s start with the first question I get pretty consistently on this topic, and that’s the following:

“My preferred return is an 8% IRR and I have a 10% cash-on-cash return in my first year of ownership, but no promoted interest is being calculated in my model in the first year. Is something wrong?”

And the answer here is no, nothing’s wrong – promoted interest won’t be earned in the first year of ownership with a 10% cash-on-cash return, even with a preferred return of an 8% IRR.

The IRR is significantly different from the cash-on-cash return in many ways, and just because the deal yields a 10% cash-on-cash doesn’t mean much about the IRR on the project. And with that, one of the biggest differences between these two metrics is that, in order for the IRR to be a positive number, this requires a complete return of capital before the IRR turns positive on a deal.

This means that, even in the case of an impressive 10% cash-on-cash return in the first year of ownership, that 8% IRR hurdle wouldn’t even be close to being met.

How This Works in Practice

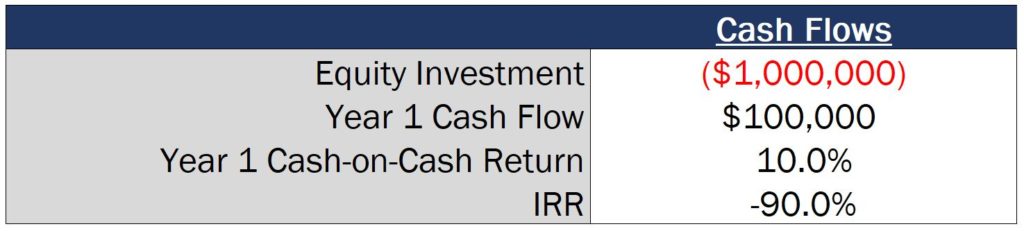

Take, for example, a $1,000,000 investment from a Limited Partner, and that Limited Partner receives $100,000 back in cash flow at the end of the first year of ownership.

Even though that investor is probably very happy with a 10% cash-on-cash return, the IRR for a $1,000,000 cash outflow and a $100,000 cash inflow exactly one year later ends up being -90%, which obviously is a far cry from the preferred return of 8% on the deal.

In fact, in that first year of ownership, the LP would have to be distributed a full $1,080,000 to hit that 8% IRR value. And aside from an outright sale of the property, this isn’t likely going to happen on most real estate deals.

Can Promoted Interest Be Earned Before The Property is Sold?

Speaking of a sale of the property, this leads me to question number two on this list:

“If the LP hits their preferred return before the sale, does the GP still earn promoted interest?”

And my answer here is the dreaded, “It depends,” but this primarily depends on the specific language in the partnership agreement that defines when promoted interest is earned.

In my experience, on individual deals, promoted interest is generally only earned at the time of what is often referred to in an operating agreement as a “capital event” on the deal.

What is a Capital Event in a Real Estate Partnership Structure?

A capital event is usually defined as one of two things – either the sale of the property, and/or a refinance of the property.

And with that, in many standard real estate JV operating agreements, promoted interest won’t be triggered until this capital event occurs, either at the time of refinance or when the property is ultimately sold to a third party.

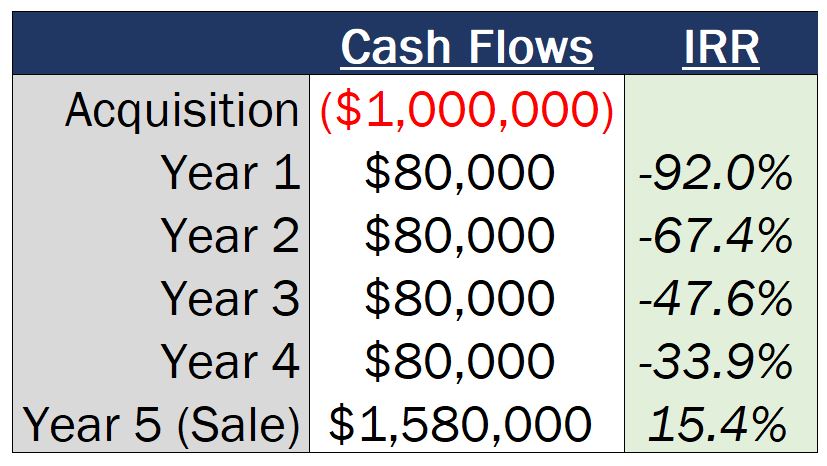

This type of scenario won’t come into play for most IRR-based preferred return structures, since a return of capital is required for a positive IRR value, which usually does require a sale of the property or (massive value creation with a refinance).

But with that said, this is still definitely something to be aware of and to consider in a planned long-term hold scenario, especially if you’re in the process of putting an operating agreement together.

Why Is The Cash-on-Cash Return The Same For The GP and LP?

Let’s move on to question three on this list, which also has to do with that pesky cash-on-cash return again:

“I’m analyzing a deal where the IRR is much higher than the preferred return, but the LP and GP cash-on-cash return are both the same numbers in my waterfall model. Why is that?”

The reason why this is the case is because the cash-on-cash return is calculated net of refinance and sale proceeds, which make up those those “capital events” we referred to earlier on in this article.

Until the preferred return is hit, many real estate equity waterfall structures call for cash flows to be split “pari passu”, or in proportion to each investor’s ownership interest in the deal, meaning that the cash-on-cash return will be the same for both GP and LP up through this point.

How This Works in Practice

In real estate partnerships, it’s common that the GP (or operating partner) will contribute somewhere between 1% and 10% of the total required equity investment. And to make up the rest of equity requirement, the LP (or non-operating capital partner) will contribute the remaining 90% to 99%.

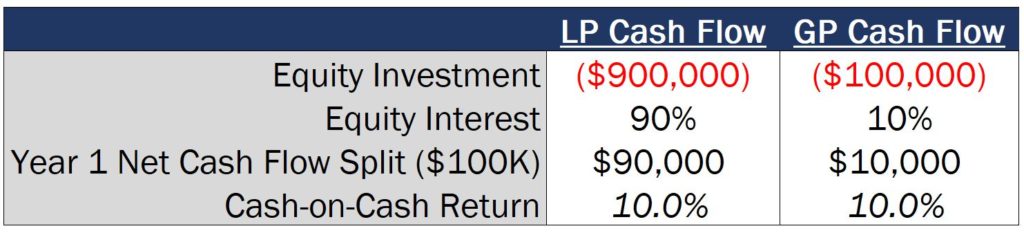

To use an example of a $1,000,000 total equity investment, assuming the GP contributes 10% of the equity, the GP would contribute $100,000 into the deal and the LP would contribute the remaining $900,000 into the deal.

And if cash flows are split pari passu based on each investor’s ownership interest in the deal, this means that a $100,000 distribution in the first year of ownership would be split 10% to the GP, and 90% to the LP.

If we run the math on the cash-on-cash returns in both scenarios, $10,000 divided by $100,000 equals a 10% cash-on-cash return for the GP, and $90,000 divided by $900,000 also equals a 10% cash-on-cash for the LP on the deal.

So, with many real estate partnership agreements calling for promoted interest to not be triggered until the sale of the property, coupled with the fact the cash-on-cash return includes operating cash flow but excludes cash flow as a result of the sale of the property, even cash-on-cash returns in the final year of ownership will still be equal between GP and LP in most waterfall structures.

How Does The Cash Flow Split Between GP and LP Actually Work?

Speaking of cash flow splits, the fourth question I’m commonly asked on this topic is some variation of:

“How does the cash flow split between GP and LP work in practice?”

Essentially, the math works out to the promoted interest being the percentage of cash flows distributed to the GP that would have otherwise been allocated to the LP, over a certain return hurdle.

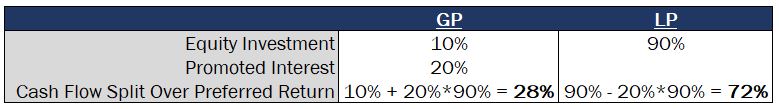

In the case of the scenario in which we had a 10% equity investment by the GP and a 20% promoted interest over an 8% IRR, a quick way to calculate the total cash flows distributed to the GP over that 8% IRR would be:

- Distribute 10% of the cash flows over the preferred return to the GP based on the GP’s original 10% equity interest

- Add 20% of what would have otherwise been the LP’s 90% of the cash flows above the preferred return hurdle to the GP’s share.

This results in 28% of the cash flows over the preferred return being distributed to the GP (10% + 20% * 90%), and the remaining 72% being distributed to the LP.

The Fine Print in JV Operating Agreements

In real estate partnership operating documents, the legal language regarding this cash flow split is often a little bit more granular than this, which tends to be what these questions are referring to.

In my experience, the language describing how cash flows are split over a preferred return or specific hurdle rate generally calls out the promoted interest being distributed directly to the “Managing Partner” (or GP’s managing entity) on the deal, and the remainder of the cash flows being split between the “Members” of the company, which generally refers to all equity investors in the project (both GP and LP), pro rata in proportion to the Members’ respective ownership share in the deal.

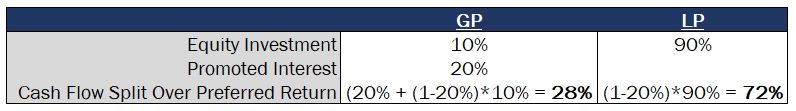

And taking a look at the numbers from this perspective, using our same example above, the cash flows to the GP would be calculated by taking 20% of all cash flows above the 8% IRR allocated towards promoted interest, plus the GP’s pro rata share of the remaining 80% of the cash flows, in proportion to their equity percentage in the deal.

Since the GP invested 10% of the equity into the deal up-front, we can calculate this cash flow split value for non-promoted funds by multiplying the remaining 80% of the cash flows (1 – 20% promoted interest) by 10% (the GP’s equity ownership interest in the deal), giving us 8% of the cash flows being allocated to the GP’s ownership share.

From there, we can add that 8% value to the 20% promoted interest value, which gets us to that same 28% cash flow value going to the GP, and 72% of cash flows going to the LP.

The math is the same and the final result is the same, but for people who are wondering the logistics behind how this actually works in most cases, this is often the legal language that details out which cash flows are allocated to promoted interest, specifically, and which are not.

Will This Waterfall Model Work For My Deal?

Speaking of legal language, the fifth and final question (and probably most important on this list) is some variation of:

“If I change X, Y, or Z part of the waterfall model we build in the course, will this still work correctly?”

My blanket answer to all of these questions is, “It depends,” which is both positive and negative (depending on how you look at it).

The negative part of this is that all waterfall structures are not created equal (far from it), so you’ll always need to check the specific legal language within your own operating agreement before finalizing any waterfall model on a deal you’re working on.

But in that same vein, the positive is that all the answers you are looking for will be contained directly within that partnership agreement on the deal, which will spell out all the details regarding how cash flows are split between partners, how promoted interest is calculated, and when promoted interest is triggered.

If you don’t know the answer about how to model a specific component of a waterfall structure, fortunately, you don’t need to spend countless hours Googling the information. And if you just look within the operating agreement on the deal, or you express the specific deal points you want to include in the partnership to your attorney that’s drafting the document, you’ll have all of the answers you need in the signed operating agreement between partners.

How To Put This Into Practice

If you’re trying to build out an equity waterfall model for a deal you’re working on, or you’re heading into an interview or have an Excel financial modeling exam coming up, I hope this is helpful in understanding some of the nuances of how equity waterfall structures generally work in practice, and how you can adjust your model accordingly.

And if you want more of a step-by-step guide on how to build an equity waterfall model from scratch in Excel, there are two Break Into CRE courses I’d recommend you check out.

The first is The Real Estate Equity Waterfall Modeling Master Class, which covers the build-out of a 4-tier, IRR-based real estate equity waterfall model. This is (by far) the most common structure I’ve seen used in the US for standalone deals, and where I’d recommend starting out first.

And if you’re working on more complex structures and want to incorporate things like cash-on-cash return hurdles, dual-preferred return structures, or catch-ups and clawbacks, make sure to check out the advanced version of the original course, The Advanced Real Estate Equity Waterfall Modeling Master Class, which will walk through how to build each of these structures step-by-step from scratch in Excel, as well.

And, as always, if you want access to all Break Into CRE courses, models, and some additional one-on-one career coaching to help you take the next step in the CRE industry, make sure to check out Break Into CRE Academy – you can check out all the details of an Academy membership here.

Thanks so much for reading – good luck on your next deal!